Faculty who are experienced in online teaching will tell you that a great deal of work and time goes into designing the course. Due to the need for enhanced organization, the fact that students work through materials at varying times (within course parameters), and the time it takes to build and deliver an online course in a Learning Management System, the course needs to be fully designed before it begins. That is not to say that changes cannot or should not be made along the way; certainly online course instructors should be responsive if something isn’t working well – this remains a best practice for all teaching. Additionally, there’s nothing wrong with, for example, recording content videos to post as the semester progresses, but to attempt to plan an online course structure, schedule, and assignments and/or build everything in Canvas “as you go” would be a mistake.

Because of the need to “front-end” much of the work, designing an online or hybrid course can feel daunting at first, but it can quickly become quite satisfying. What might be lost in spontaneity certainly is gained in coherence! Planning the course in this holistic way facilitates a sharper focus on the alignment of learning goals or outcomes, learning assessments, and learning activities. And this is where your design process should begin.

Quick Tips from Learning Academy Faculty Consultants for Online Teaching

User experience is key! In addition to organizing your shell in weekly modules with clear written and recorded video instructions, make sure that everything students need is accessible when they need it. Link to assignment instructions, embed videos and files, and do not send students on an Easter Egg Hunt to find what they need to do the work. – James Hutson, Associate Professor of Art History

I always begin courses with a “Get Started Here” module, which serves as the course introduction and includes helpful links. Courses are set up in weekly modules, which includes all of the content and assignments the students need for each week. Each module includes an overview, where I upload either a video or narrative explanation of that week’s objectives and content. Each module concludes with readings for the following week. – Michelle Whitacre, Assistant Professor of Teacher Education

Topics in Course Design

Begin with the End in Mind

For any course design, we recommend using an approach called Backwards Design, articulated by Wiggins and McTighe in their book, Understanding by Design. This Learning Academy Tutorial and accompanying templates should be enough to get you started, but see additional resources to dig deeper.

A note: The terms Learning Goals and Learning Outcomes are sometimes used interchangeably. Here, learning goal is used to describe something an instructor hopes to achieve in a course, whether measurable, measured, or not (e.g., This course strives to expose students to global perspectives on constitutional law.) while learning outcome is used to describe something more specific and measurable that students will be asked to do and on which they will be assessed (e.g., Students will be able to evaluate the public policies of a precedent case or rule and assert appropriate arguments to support some application of a precedent case to a legal controversy.)

Backwards Design Video Tutorial

Arizona State University provides guidance on how to ensure measurable learning outcomes in 4 Easy Steps.

Simple Backwards Design Template (PowerPoint)

If you want to take it one step further, you can include your Learning Outcomes in Canvas and link/align them to assessments, assignments, and even rubrics.

References and Resources for Learning More about Backwards Design

Once you’ve gotten started on Backwards Design, you may want to shift to a more detailed template to design in more detail. The detailed planning template in the following section will help you to develop your course one module at a time.

Modules: The Building Blocks of Online Course Design

A module is the basic building block of an online course. It organizes a course into segments by a span of time (e.g., weekly module), topic (e.g., Virtue Ethics), chapter (e.g., Chapter 1), unit (e.g., Qualitative Research Methods), or course element (e.g., Discussions). An instructor may also choose to use pages instead of or in addition to modules to create an organizational scheme, but if you’re new to online teaching the module is probably the most straightforward way to go.

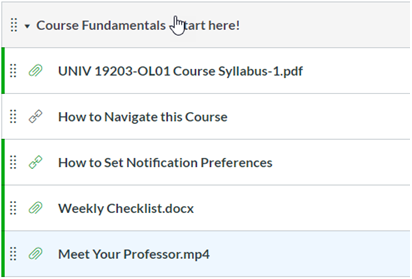

Below is an image of a course that begins with a module containing course introductory materials and proceeds with modules organized by week and topic (i.e. one topic per week):

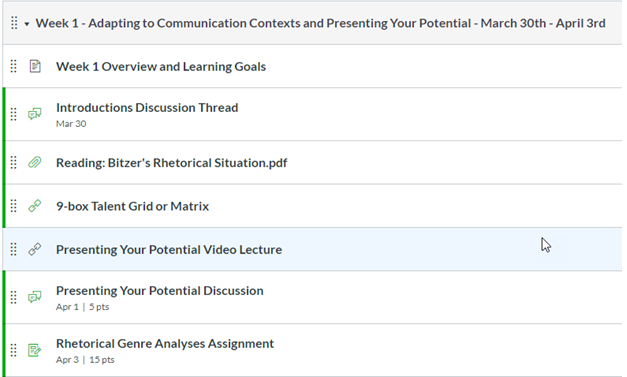

The first week’s module, shown in the second image, begins with an overview of the week’s topics and activities and learning goals for this segment of the course. This provides an orientation for the students to what they will be doing for the week and why, just as you might provide in your on-ground course at the start of a new week, chapter, unit, etc. The module also includes a discussion board for students to introduce themselves to the instructor and one another, the week’s readings, a video-recorded lecture, a content-focused discussion board, and an assignment.

View more examples from courses at Northwestern University or check out Canvas Commons. When you’re logged into Canvas, you can go to Canvas Commons and search for “template” or “sample course” to view various ways to organize a course.

You’ll find helpful information on how to build modules in Canvas in the Building Your Online / Hybrid Course drop down below.

Before you move on, check out this very brief and very helpful section on Course Organization from the ACUE Online Teaching Toolkit. It provides 3 Quick Tips to help you simplify your design.

What to Include in a Module

It is a good idea for planning purposes and for student orientation and metacognition to provide learning goals or outcomes (or both) for each module. These goals/outcomes should guide what you provide and ask students to do within the module.

A helpful framework for ensuring a robust a module is to plan for how students will interact with content, with you, with one another, and, if appropriate, with outside parties or resources for a given topic, lesson, or unit (Access Ebsco and then search for "Online Teaching at its Best: Merging Instructional Design with Teaching and Learning Research" by Nilson and Goodson).

Learning Activities/Interactions/Assessments

- Student-to-Content

- Examples: Read a chapter or article, view a micro-lecture from instructor, view a TED talk, complete a virtual lab, complete a practice problem set, complete an analysis of sample speech, take a quiz on the readings, read a case study and answer questions.

- Student-to-Student

- Examples: Meet (virtually) with project team members, post twice to the discussion board about the week’s topic, complete a peer review assignment

- Student-to-Instructor

- Examples: Project update meetings with instructor, instructor feedback on problem set, Q&A session with instructor about lab, submit content clarification questions and then view content clarification video from instructor

- Student-to-Other

- Examples: Experience the Tour a Refugee Camp online simulation, find and contact a professional who holds a job you’d like to know more about to ask for an informational interview, visit a non-profit organization’s website and complete the organizational analysis assignment

To best “translate” your course content, activities, and assessments from on-ground to online or hybrid, you should consider the nature of your course. Is it intended to be a seminar-style course centered on discussions (e.g., British Literature 1)? Is it a course that requires a lot of instructor modeling and coaching (e.g., College Algebra)? Is it a course that lends itself to semester-long independent projects (e.g., Research Methods in Sociology)? Does it require hands-on activities or performance of kinetic tasks (e.g., Advanced Costume Design)? We’ll come back to various ways to deliver content, create engaging activities, and design effective assessments in later sections, but for now let your answers guide your initial planning of module content and activities.

*A note about synchronous sessions: In a fully online course, we do not recommend requiring students to attend synchronous sessions as this can place a hardship on students who live in different time zones as the instructor or who have work or caregiving responsibilities. For online courses, synchronous sessions may be effective as optional, supplemental activities and/or if they are recorded for viewing by students who cannot attend them.

Example Module Content by Course Type

Discussion-based Courses

If your course is discussion-based, a module might contain, for example:

- an overview

- a reading (student-to-content)

- A video wherein the instructor covers content and/or models textual analysis (student-to-instructor)

- Hybrid option: Students view the video, submit questions online, and prepare thought-provoking questions to guide on-ground discussion. The face-to-face session is used to answer questions students submitted, clarify confusing points in the content, elaborate on the content or guide students in textual analysis, and discuss answers to the questions students brought to class (student-to-instructor, student-to-content, student-to-student).

- an assignment that asks students to analyze some text or artifact according to the reading and instructor video (student-to-content) and for which you provide feedback (student-to-instructor)

- a discussion board activity where students choose an additional artifact or text to analyze, post their analyses, and provide one another feedback on those analyses (student-to-content, student-to-student). It’s recommended that in the latter activity the instructor join the discussion, as well (student-to-instructor).

Problem-solving-based Courses

If you teach an online or hybrid course that is centered on instructor modeling and coaching of problem-solving, like math or a mathematical based science, a module might contain:

- an overview

- a reading (student-to-content)

- a video of the instructor demonstrating the solving of equations with audio narration of the process (student-to-instructor, student-to-content)

- an asynchronous discussion thread for Q&As (student-to-instructor, student-to-student, student-to-content)

- Hybrid option: Students complete the three activities above and then an on-ground session is used to address common questions, reinforce student understanding through elaborated content coverage and/or instructor demonstration (allowing students to ask additional questions along the way), and coaching as students work through problems (student-to-instructor, student-to-student, student-to-content).

- an assignment or quiz wherein students complete a set of practice problems and explain/show their work (student-to-content) and receive feedback (student-to-instructor)

Performance-based Courses

Courses that are performance-based are certainly among the most challenging to design for an online format, though the hybrid format (usually) allows for live, in-person student performances. Fully online courses can rely on video technology to share performances. A module for this type of course might include:

- an overview

- a reading (student-to-content)

- a video of the instructor or someone else explaining and performing a task (e.g., joint mobilization technique) or giving an artistic performance (e.g., sculpting technique) (student-to-content)

- an asynchronous discussion activity wherein students are asked to post one “muddiest point” or something they are struggling and respond to one another’s posts, while also receiving further instruction or clarification from the instructor (student-to-student, student-to-instructor)

- an assignment wherein students are asked to perform a task or deliver a performance via video (student-to-content), write a reflection, and receive instructor and peer feedback (student-to-instructor, student-to-student)

- Hybrid option: Students do the reading, view the video, and post to the asynchronous discussion online. Then, the on-ground session is used for students to perform or complete tasks requiring specialized equipment (student-to-content). Students can receive feedback in real time and/or post-performance via online tools (student-to-instructor, student-to-student).

If you teach in Fine Arts or if your course has a lab, you might be interested in Inside Higher Ed’s Remotely Hands-On: Teaching Lab Sciences and the Fine Arts During COVID-19.

Project-based Courses

For courses wherein a project serves as the primary source of learning and assessment, a module might contain the following:

- an overview

- a learning activity wherein students are asked to review and reflect on an example of a project similar in some way to the ones they are working on (student-to-content)

- a discussion board where project groups are asked to post about the progress they’ve made and the challenges they’re facing as well as offer tips and resources to one another (student-to-student)

- Hybrid option: Groups complete the two activities above online and in the on-ground session the instructor spends time discussing with students the strengths and weaknesses of the example project to clarify expectations, addressing common issues groups are experiencing, and providing additional guidance and feedback to the class.

- synchronous project team meetings with the instructor to get feedback and guidance (student-to-instructor)

- an assignment in which project groups must find and contact an external professional in your field who can serve as an informational resource for their project (student-to-other)

Learn more about project-based learning in online courses.

How to Design for a Hybrid Format

For blended learning, the focus should be integration and maximization of each learning modality. Students should feel as if time is well-spent online and in-person; therefore, activities that occur via the different modalities should not be redundant, but complementary.

Stein and Graham (2014) argue that if you’re converting an on-ground course to a hybrid one, the most obvious approach –to simply replicate on-ground activities online – will not create the best learning experience. “In the worst case, the resulting blended course will not measure up to the rigor, engagement, or outcomes of the onsite course” (p. 66). They encourage instructors designing blended courses to avoid this and these other common mistakes:

- Creating too much work for students by simply adding online or onsite activities to an existing course design

- Using technologies without purpose

- Implementing onsite activities online that simply don’t work well in a virtual and/or asynchronous format

To avoid these pitfalls, rethink the design of your course starting from the learning goals and outcomes, using the Backwards Design approach described in the section above, and consider the benefits of each modality, as well as how they complement one another, as described below. Maintaining focus on the learning goals and outcomes and ensuring that these guide decisions about assessments and activities will keep a course design on track.

A Decision-Making Process

- As always, when you are designing course components, start from your learning goals and outcomes. What is it you want students to know or be able to do?

- Then consider how you’ll assess their knowledge or skills. What evidence of learning will you collect?

- Finally, how can they best learn what they need to learn in order to demonstrate their knowledge or skills?

- Once you have those things in place, you can consider the nature of your two modalities to determine which of your learning activities and assessments are best suited for online compared to a face-to-face session.

Consider these advantages of the online modality

- You can hear from each student. Whereas in a synchronous discussion, there are usually some students who speak and others who stay quiet, online discussion boards may better facilitate an inclusive discussion.

- Relatedly, students who are quiet because they feel anxious, embarrassed, or because they need more time to formulate a response can more easily join the conversation.

- Students can consume straightforward content efficiently and, as a result, be prepared to discuss or apply it, or build on it to learn things that are more challenging.

- While consuming content, students can more easily access outside sources that might help them to better understand what you’ve provided (e.g., they can quickly look up a term they’re not familiar with or even refresh on basic concepts that your course assumes they know).

- Students can complete formative or summative assessments without using class time to do so.

- It is easier to provide individual feedback to students.

- Students have more time to reflect on what and how they are learning and to identify points of struggle, lingering questions, or connections.

Consider these advantages of an on-ground session

- Instructors can present content through demonstration and dialogue with students, which can provide a richer interaction with that content, and can especially help students to comprehend challenging content.

- Instructors can observe students and more easily identify moments of confusion or concern so that they can pivot to provide more information, different examples, etc. to aid student learning.

- Synchronous group discussions facilitated by an instructor allow for more spontaneous, synergistic, and elaborative consideration of the material.

- Students can access equipment or space for performing tasks that may be unavailable to them online.

- Students can receive real-time coaching from the instructor or one another.

- Students can present or perform for a proximal, live audience, which may be important for preparing them for success outside of the classroom.

- Multiple student groups can work together simultaneously, teach each other, and receive immediate feedback about comprehension or application of material.

- It can be easier to build rapport and a sense of community through in-person interaction.

Best for On-ground?

The best use of on-ground sessions will differ by discipline, course-type, and course level, but it is safe to say that things like group discussion, debate, instructor demonstration, instructor coaching, student presentations or performances, lab experiments, Q&A sessions, and collaborative activities (except those that make good use of online technologies like wikis) are a good use of on-ground sessions.

Best for Online?

Things like reading, reflections, self-assessments, quizzes, viewing videos, consuming straightforward lectures, exploring web-content, sharing multi-media products students have created (e.g., infographics), peer-reviews, and activities or assignments that require ample time or access to outside resources are well-suited for online course components.

One proven approach to hybrid or blended learning is Just in Time Teaching, wherein the online components prepare students for the on-ground components and allow the instructor to tailor the on-ground activities (including lecture) to “meet students where they are.” The “hybrid option” bullet points in the previous section, Examples by Course Type, follow this approach. You can access an ebook at Ebsco. Access Ebsco and search "Just-in-time teaching: Across the disciplines, across the academy."

Tip for Coherence: When you are in a synchronous session, refer to what has occurred or will occur online/asynchronously and explicitly draw connections and create a sense of seamlessness for students. If you are able to refer to specific student comments or questions posted online while you’re discussing things in class or vice versa, even better.

Now that you’ve started on the Backwards Design Process using the simple template in the previous section on that topic, try out this more detailed planning template for online or hybrid courses, which also contains examples, that can assist you as you plan modules/week and the assessments and activities that will occur online and on-ground.

You can view example syllabi for Hybrid/Blended Courses (Example 1).

NOTE: Because the format of courses with on-ground enrichment in the Fall will be challenging, given that some students will be in the room, some will be synchronous online, and others may watch the recording of the on-ground session later, design of a session will be challenging! This example will likely prove very helpful as you think through how to do this in your courses.

References and Additional Resources

Stein, J. and Graham, C. R. (2014) Essentials for blended learning: A standards-based guide. Routledge, NY.

Blended Learning in Practice: A Guide for Practitioners and Researchers

Blended Learning in Higher Education: Framework, Principles, and Guidelines

How to Design and Teach a Hybrid Course: Achieving Student-Centered Learning through Blended Classroom, Online and Experiential Activities (available through the Lindenwood Library)

Creating an Online or Hybrid Course Schedule

The schedule you create for your course and your students should be as straightforward and consistent as possible in order to help students stay on track. Try to view things from the student’s perspective. How would a student know when to do what? How can you make things like due dates obvious? Can you include information about what they should be doing on a given day even if there is no official due date? Remember that students won’t necessarily have the ability to rely on regular, synchronous communication with you to help guide them, so your schedule and course set up in Canvas will need to serve as their guide. It’s a great idea to use consistent due dates when possible so that there is a rhythm to the course that enhances students’ ability to stay on track.

Example Course Schedules

Sample Partial Schedule for an Online Course provided by Lindenwood Online

Example of full schedule for an online course.

Here’s what a week’s worth of a hybrid course might look like:

Week 1 – August 24-30: What is Persuasion?

By Monday

- Take Self-assessment on Understanding Persuasion (online) – Due Monday at midnight CST

- Read Chapter 1

- Begin viewing micro-lectures (online videos)

By Tuesday

- Finish viewing micro-lectures (online videos)

- Submit brief summary of each micro-lecture (online assignment) – Due Tuesday at midnight.

- Begin responding to questions/prompts embedded in the lectures (post to Lecture Reflections Discussion Thread)

By Wednesday

- Finish posting your responses to questions/prompts embedded in the lectures (post to Lecture Reflections Discussion Thread)

- Respond to at least one other students’ post for each lecture (you’ll be responding 3 times minimum) – Due Wednesday at midnight.

- Begin locating or formulating a message or communication scenario that you think is worth evaluating together as a class (detailed instructions provided in discussion thread).

By Thursday

- Post a link to or describe some message or communication scenario you think is worth analyzing (online). We will use this in our on-ground activity during Thursday’s F2F session. – Due Thursday by 1:50 p.m.

- Attend the synchronous class session (on ground and online) – Thursday, 2-3:15 p.m.

- If it is your assigned day, attend in person. If it is not your assigned day, attend via Canvas Conferences. If you will not be attending in person and cannot attend synchronously online, you can view the recorded session in Canvas Conferences sometime on Thursday.

By Friday

- Complete and submit Message Evaluation Assignment (online) – Due Friday at midnight, CST

Weekend Homework

- Review any discussion board posts you missed (online) and instructor feedback on assignment (online)

- Begin exploring the next module and reading the next chapter (online)

And this hybrid course syllabus contains a full, detailed schedule.

Tips on Helping Students Navigate your Online/Hybrid Course

- Provide an overview in your “start here” module or on your homepage, perhaps in video form, on how to navigate the course, highlighting important things to which students should pay special attention (e.g., each week there are two due dates, one on Wednesday and one on Sunday)

- If hybrid, make sure to mark on your course schedule which activities will occur online and which will occur during on-ground sessions.

- Use the “rule of three” to ensure students pay attention to important course information. If there’s something important they need to know, do, or avoid, say it in the syllabus, say it in the module, and say it again in an announcement before an assessment (teaching tip provided by Ana Schnellmann, Professor of English at Lindenwood.

- At the start and/or conclusion of each module, make connections for students – or ask them to make connections – across course material so that they see the progression from week to week/module to module

- Consider providing some form of overview or introduction to each module

- Make similar connections and take chances to reorient students during on-ground sessions and/or via weekly announcements

- Make your course schedule into a checklist. Students can print or use online (you can use boxes in place of bullet points or they can convert bullet points to checkmarks or strike through a line when they’ve completed a task)

- You might even include a weekly to-do list at the start of each module so that students don’t need to refer back to the syllabus, but can see what needs to be done during the week right in that week’s module

- In addition, use the “to-do list” function in Canvas for assignments with due dates (click “include in students’ to-do list” when you’re creating the assignment or discussion board)

- Include learning outcomes or learning goals within each module so that students understand the purpose of readings and activities for that section of the course.

Designing Learning Content for an Online or Hybrid Course

Creating and/or finding content for your online or hybrid course is an important part of course design. Content needs to be especially engaging and clear if students will be consuming it online, asynchronously.

Getting students attention may seem harder when you’re not in front of them in an on-ground classroom, but it is quite important as “student attention precedes motivation, engagement, and learning” (Nilson & Goodson, 2018, p. 110). Consider the ways you strive to capture and keep students’ attention in your on-ground courses and make sure to include these same strategies when you’re designing content and communications for your online or hybrid course. For example, don’t forget to:

- Express enthusiasm for your subject

- Provide varied examples and metaphors to help students understand new concepts

- Share stories and cases that bring material to life

- Discuss your own academic discoveries, successes and challenges

- Draw upon a range of activities

- Pose thought-provoking questions

- Challenge students’ existing ideas and mental models

- Vary the ways you present material

Some options for delivering content in an online course include:

- Providing readings via printed text, ebook, scanned articles, or links to online articles.

- Recording short video or audio lectures (you can record audio narration for your PowerPoint slides within PowerPoint; Insert > Audio > Record Audio) (more tips for video recordings can be found in the Build Your Online Course section)

- Consider embedding a question or assignment prompt in your lecture. Ask students to take some action to apply or reflect on what you’ve presented. Once students know your recordings contain prompts, this also becomes a motivator for them to pay close attention to them. Alternatively, provide students with questions beforehand that they must answer using the lecture in order to focus or ensure their attention.

- Posting PowerPoint slides or other content presentation formats with accompanying notes in text format.

- Hosting synchronous lecture/discussion sessions via Canvas Conferences or other technology that are recorded for viewing by students who were unable to attend synchronously.

- Linking to or embedding Open Education Resources (OER) like videos, modules, games, lectures, etc. The Lindenwood Library is dedicated to helping instructors locate OER. See their Library Guide for more information.

- A great resource for OERs is MERLOT. Here, you can find (by discipline) assessments, learning activities (example case study in public health), and “instructional objects” like explanatory animations (example on mitosis), tutorials (example on plagiarism), and entire modules (example on linear algebra). There are also discipline-specific OER sites like Digital Pedagogy in Humanities or MIT OpenCourseWare (sciences and engineering)

- Linking to an educational website.

- Creating or finding infographics explaining concepts or processes.

Designing Effective Assessments

Online and hybrid course formats can pose some challenges to designing assessments, but also open up possibilities for innovation. Students can utilize In the case of hybrid courses, the online modality provides a way for students to complete assessments without using valuable on-ground class time.

Academic Honesty

Often, faculty worry that online assessments are more susceptible to academic dishonesty than those that occur on-ground. In many cases, students will have more opportunities to use outside sources for assistance on quizzes, exams, or other assignments they normally complete under supervision in an on-ground class. Moreover, in part due to uncertainty and anxiety they may be experiencing, they could be more motivated than usual to take shortcuts.

To some extent, instructors must accept that there is no way to eliminate students’ ability to cheat in an online course (also true for on-ground courses) though there are things they can do to discourage it. If students have not taken online courses before, they may need clarity on what constitutes dishonesty in online assignments like discussion board posts, so consider articulating this. If your main concern is what to do about academic dishonesty on exams, below are some ideas, considerations, and resources to help you think through options.

Discouraging Dishonesty in Online Exams

If you use an online exam, there are a few things you can do in Canvas to discourage academic dishonesty.

- Using multiple, low-stakes quizzes rather than infrequent, high-stakes exams lowers the pressure students might feel to commit dishonesty in order to perform well. This approach, which gives students practice is information retrieval, also improves students’ retention of knowledge (Roediger & Butler, 2011).

- You can create a test bank and randomize questions. (You might be able to supplement your exam questions with those provided by your textbook publisher).

- Use

Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy. - If your exams include problem-solving questions (e.g., Math), ask students to show their work (they could submit a written explanation or a video of them explaining orally).

- Here’s a helpful guide to writing effective exam questions; many of the strategies for doing so will also make cheating more difficult.

- You can use the "Lockdown Browser" function on the left side of the screen to prevent students from looking up answers online (using the device they’re taking the exam on, anyway).

- You can shuffle questions and set time limits, though you are likely to need to set different limits if you have students who have accommodations.

Additional ideas and considerations from Purdue's website:

- Allowing exams to be open-book/source: Assume students will use resources while taking an exam, and even encourage them to do so. Try to ask questions that probe deeper levels of knowledge and understanding, enabling students to apply, assess, and evaluate concepts and facts in meaningful ways. Encourage students to share and cite where they get information from and what resources they use. You might be interested in this Faculty Focus article that provides a rationale for going with open-book testing.

- Use student-generated questions with explanations: Instead of trying to ensure everyone answers your limited number of questions on their own, ask every student to create their own question with an explanation of how it would assess a certain topic or skill in a meaningful way. You can also assign students to answer each other’s questions and state whether those questions actually do assess these skills in appropriate ways.

- Consider question formats leading to essays, videos, pictures, and other personal responses: If your class lends itself to it, having students express their learning through essays, videos, pictures, or other personalized forms of writing / speaking / communicating means that everyone needs to create their own. You can also have students post their responses for each other and assess each other’s work through peer grading. Rubrics can help guide students as they develop such work, give each other feedback, and, of course, allow your teaching assistants and you a consistent method of assessment.

- Use an alternative to an exam to assess student work: You might conclude that an online exam is not the best way to observe students’ knowledge or skills while maintaining academic integrity. Maybe a writing assignment, project, or video response to an open-ended question could work better.

- This list of alternatives to traditional tests might spark an idea for you.

- Scaffolding assignments is a strategy that’s not only helpful for student learning, but one that discourages academic dishonesty.

Roediger, H. L., and Butler, A. C. (2011). The critical role of retrieval practice in long-term retention. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 15, 20–27. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2010.09.003

Creating Authentic Assessments

We recommend considering Authentic Assessments for your courses. View this Learning Academy tutorial to learn what makes an assessment authentic, how to design one, and the benefits of using them.

Authentic Assessments Video Tutorial

Below are examples of authentic assessments.

- Here’s a Service Learning Project example.

- In this authentic assessment, students created their own blogs.

- Read about Lindenwood faculty member, Barbara Hosto-Marti’s authentic assignment revision in The Learning Log.

Still not sure if it’s the approach for you? Read about the comparison of authentic assessments to traditional tests on this page from Indiana University.

References

Fox, J., Freeman, S., Hughes, N., Murphy, V. (2017). “Keeping it real”: A review of the benefits, challenges and steps towards implementing authentic assessment. AISHE, 9(3), 3232-32313.

Keeling, S.M., Woodlee, K.M. and Maher, M.A. (2013). Assessment is not a spectator sport: Experiencing authentic assessment in the classroom. Assessment Update, 25(5), 4-5, pp. 12-13.

Larmer, J. (2012, June 5). PBL: What does it take for a project to be "authentic?" Edutopia. https://www.edutopia.org/blog/authentic-project-based-learning-john-larmer

Palmer, S. (2004). Authenticity in assessment: Reflecting undergraduate study and professional practice. European Journal of Engineering Education, 29(2), pp. 193-202.

Wiggins, G. (1989). A true test: Toward more authentic and equitable assessment. The Phi Delta Kappan, 70(9), 703-713.

Using Group Assignments in Online or Hybrid Courses

Group assignments can be challenging for instructors and students to manage, but can provide excellent learning opportunities. Students engaged in collaborative learning acquire and retain more knowledge than those working individually and develop increased problem-solving and reasoning skills (Johnson, et al., 2014). Group work can be done in online or hybrid courses and may be especially important to assign in these formats in order to help students make connections with one another. Read about ways to design effective team projects for online courses before getting started.

Johnson, D. W., Johnson, R. T., & Smith, K. A. (2014). Cooperative learning: Improving university instruction by basing practice on validated theory. Journal on Excellence in University Teaching, 25(4), 1-26.

Designing Rubrics

It is recommended that instructors create rubrics for authentic assessments (Wiggins, 1989), discussed above, but clarity in evaluation criteria is helpful to the students being assessed and the instructor doing the assessing no matter what sort of assessment is used. Even weekly discussion board posts should have a rubric. Students, then, know what exactly they’re after when they formulate posts and instructors can recognize and evaluate quality posts (and those that aren’t), and provide targeted feedback, more efficiently.

Nilson and Goodson (2018) say that in order for instructors to provide targeted feedback that helps students to improve across assessments, students must be clear on what elements their work should accomplish, what is should contain, and what questions it should answer. Rubrics describe these things in detail for students, explaining characteristics of excellent and poor work, and everything in between. Rcampus.com contains countless sample rubrics, including one for a weekly discussion board.

Nilson, L. B., & Goodson, L. A. (2018). Online teaching at its best: Merging instructional design with teaching and learning research. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons.

Designing Learning Activities for Online or Hybrid Courses

We’ve all heard the time active learning, but what does that really mean? When students are engaged in learning activities that involve them in ways beyond receiving information via transmission (i.e. the instructor tells students something and they listen to and comprehend it), they are actively learning (Bonwell & Eison, 1991).

Introduction

Learning becomes even more active if students are challenged to think about what and how they are learning, and their own mental models attitudes, or values. This kind of learning can occur during nearly any kind of activity from lecture (yes, lecture, as long as it is interactive!) to demonstrations to small group work, to case study analysis, to application exercises.

You may have been incorporating active learning strategies in your on-ground courses for some time, but perhaps you struggle to imagine creating an active learning environment in an online course, but there is often a relatively easy and effective way to translate activities. The hybrid format is an ideal format for active and collaborative learning activities, as the onsite, synchronous sessions may be best used for application of and reflection on content.

References

Bonwell, C. C., & Eison, J. A. (1991). Active Learning: Creating Excitement in the Classroom. ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report, Washington DC: College of Education and Human Services and Human Development, George Washington University.

Active and Collaborative Learning Activities

There are many clever, simple, and useful activities that can be – and have been – used in online courses to encourage active and collaborative learning.

The book, Collaborative Learning Techniques: A Handbook for College Faculty, by Elizabeth F. Barkley and K. Patricia Cross (2014) reviews many of these techniques like round robin, buzz groups, and critical debates, and outlines how best to implement them in an online course. The ebook is available through the Lindenwood Library.

The K. Patricia Cross Academy has videos and downloadable guides and templates for dozens of active learning activities like the jigsaw method, lecture wrappers, group grids, and quick jumps.

Content-Specific Application Exercises

In addition to the “generic” activities that will work with most content and disciplines covered in the resources listed above, consider what kinds of application and reflection exercises you can design that are specific to the content you cover in your course.

For example, if you teach a course in research methods, a specific application activity might be:

Ask students to determine the best methodology to answer research questions or prove hypotheses you provide and then explain their choices. Alternatively, you could ask students to generate the research questions and hypotheses themselves, exchange with another student, and have them determine the best methodological approach and provide their rationales.

Students could do this either before or after you present content. To generate ideas for these specific application exercises, ask yourself questions like:

- Now that students have heard from me (or the text) about X, how can they put that knowledge to the test?

- How can students come to see a process in action or perform it themselves?

- How can students approach knowledge construction inductively; that is, begin from examples or cases and draw conclusions?

- What do academics or industry practitioners in the field to apply disciplinary knowledge and how can students replicate that on a small-scale?

Incidentally, you’ll end up designing learning activities, and possibly even assessments, that are characterized by authenticity (see Designing Effective Assessments section above).

Reflection Questions to Encourage Active and Self-regulated Learning

One way to encourage active learning and to help students observe and assess their own learning process is to ask them to reflect on what and how they are learning. Drawing from many sources, Nilson and Goodson (2014, pp. 91-92) provide a list of questions that students might answer after content presentations:

- What is the most useful or valuable thing you learned?

- What are the most important concepts or principles?

- What do you not understand clearly?

- What helped or hindered your understanding?

- What idea of fact surprised you?

- What comparisons and connections can you draw between this new material and your earlier learning in this course and other courses?

- What stands out in your mind?

- How did what you learned confirm or conflict with your prior beliefs, knowledge, or values?

- How did you react emotionally to what you read, heard, or watched?

These could be used to generate discussions or for an individual assignment.

References

Nilson, L. B., & Goodson, L. A. (2018). Online teaching at its best: Merging instructional design with teaching and learning research. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons.

Tips for Designing On-ground Learning Activities with Social Distancing and Fluctuating Attendance

A recent Inside Higher Ed article asked, Can Active Learning Co-Exist with Physically Distanced Classrooms? While active learning activities are typically a perfect way to spend time in on-ground sessions of hybrid courses, this will be trickier as students and instructors must observe social distancing guidelines and because instructors may see varying and unexpected numbers of students in attendance during on-ground class meetings. This can make planning time well-spent a real challenge for instructors. Consider these tips as you navigate this reality:

- Know that your volume will need to be louder than normal if you’re wearing a mask and be ready to repeat student questions aloud or on the board so others can see/hear what is being asked.

- Use the board, Canvas chat, or some other medium to summarize discussion highlights. You can also ask a student to do this for you.

- Choose active learning activities that do not necessarily require small group interactions. For example, asking students to write a minute paper and then discuss as a whole class is active, engaging, and does not require proximity to others.

- Avoid planning activities that require a minimum number of students to be present in a room together or that require students to be in close proximity.

- Understand that there may be students joining virtually, so whatever activity you plan for the on-ground session will need to include students attending at a distance; therefore, if you have only a few students in the room, there should still be a way for the activity to be accomplished.

- If you’ve planned a complex activity that won’t work with too few students in the room, have a simple back-up plan – the simplest forms of active learning are probably discussions, interactive demonstrations (e.g., solving problems while taking student questions), and coaching (e.g., providing feedback and guidance to students as they work).

- Ask students to do something to prepare for the synchronous session. It could be that you ask them to generate a thought-provoking, discussion-starter question to “bring” to class (whether they attend on-ground or online) or submit online before class; you might even gamify this by awarding points to the student who poses the most insightful or probing question.

- Explore and use technologies that allow you to poll students or that allow students to collaborate at a distance.

- Use the room wisely. If you want students to work in pairs or small groups and you have a large enough space and few enough students attending in person, spread students all around the room and ensure they maintain distance. If volume becomes an issue during group work, ask them to communicate via Canvas chat, text, or some other technology.

How to Best Use Online Discussion Boards

Discussion boards are an important way to facilitate collaborative active learning and collaboration in an online or hybrid course, but in order to do so they must be designed to engage students with the content, with one another, and with their instructor so that students do not approach them as a series of obligatory, disconnected posts.

Before you design prompts, consider these 4 types of discussions in online courses.

Next, consider these strategies for making a discussion board a bit more engaging or useful than the typical, “post a question or comment on the chapter’s content” kind of prompt:

Use a modified Jigsaw method (for an explanation of a typical jigsaw method, see K. Patricia Cross Academy) to facilitate collaborative information sharing.

Students are organized into small groups, and each one is provided with one of the smaller parts of the content. Students work together (via chat, video conferencing, phone, etc.) to understand the information. They also decide how to best share this knowledge with others who do not have the information. Then, groups present information via a discussion board (in text, video, or audio format) and take questions from other students. The instructor can also post questions for the groups to answer or take questions from the groups to help solidify understandings.

Analyze a text/artifact/data set

Either provide a text, artifact, or data set for students to analyze or ask them to find one to analyze. Analyze it together or individually via discussion board, asking students to comment on, challenge, or ask questions about others' analyses.

Collaborative problem solving

Students work individually or in pairs or groups to solve some problem posed by instructor; each works to solve the problem and posts their solutions; each student/group required to comment on two other groups’ posts.

Point/Counterpoint

Students are assigned either point or counterpoint role for a discussion of material. Point person makes an observation, argument, analysis, suggests a research idea, solution to a problem, or in some other way applies a concept. The counterpoint role responds in disagreement, offering another take on things.

Stump Your Peer

Students create a challenging question based on the lecture / reading content and pose the question on the discussion board. Other students try to answer the questions. The instructor joins in to clarify or elaborate. (These questions can also be used in subsequent quizzes or exams.)

Muddiest point

After reviewing the content, students post about what is still unclear to them and the instructor responds with clarification. Option: You could have students attempt to clarify for each other and then step in after a few responses to indicate whether they’re on the right track.

Case-based discussions

Provide a case study and have students analyze it or answer specific questions individually or together via discussion board.

Synchronous Small Group Discussions in Online Classes

Breaking students into small groups for discussion and problem-solving is a time-honored technique in the face-to-face classroom. It allows students to engage with each other and the instructor to take a step back from driving discussion to let the students lead. Small group discussions in the online classroom, though, can seem more difficult to execute—breaking students out is not quite as simple as numbering them off, and it can be difficult to monitor multiple discussions simultaneously.

However, the benefits of small group discussion in online synchronous sessions remain the same—and add the ability for students to interact and connect in ways that the online environment often limits. Students don’t have the opportunity to chat before and after class just because they’re in the same space, so providing them a chance to interact opens up the possibility for students to connect with potential study partners, back-up note-takers, and even eventual friends.

Faculty in the Faculty Swear and Share are reporting great success with Big Blue Button breakout rooms for encouraging student discussion and engagement during synchronous meetings. If you want to encourage your students to interact with one another through small-group discussion but haven’t yet discovered the magic of breakout rooms, these simple steps for creating and managing breakout rooms can help. (There’s also a handy video tutorial on YouTube narrated by BBB owner and general fix-it person Fred Dixon.)

When assigning small group discussions in your synchronous or hybrid class, consider the following tips for assuring an effective outcome:

- Make sure the goal of the small-group discussion is clear so that students don’t waste time debating the assignment

- Assign roles, or ask students to assign roles for reporting out—team leader, note-taker, reporter, for example

- Check in with each group as they discuss. Students in online classes crave interaction with the instructor and small group discussions can provide that opportunity.

Further reading: Faculty Focus provides an excellent and detailed overview of things to consider when deploying small groups in the online environment.

Additional uses for a discussion board provided by Meri Marsh, Associate Professor of Geography and Learning Academy Faculty Consultant for Online Teaching

Method 1: Use discussions as a means for students to interact with course materials in a different (and more public) way than papers/reflections/assignments.

Example prompt:

Between the Introduction and the 1st chapter in your text ("The Wastemakers"), there's a powerful quote by Dorothy Sayers. Take a minute to re-read it before participating in this discussion.....

Have you ever noticed that the term, "waste" takes on different meanings in different contexts? "Wasted" time has a much different connotation (more precious) than "wastepaper" basket. Waste, when we're talking about things we dispose of in a trash bin, isn't nearly the same as other materials that are "wasted" (time, talent, resources).

In this discussion, I want you to respond to the following:

- WHY does waste mean something different when we're talking about goods (like food containers, junk mail, and paper napkins) than when we're talking about less tangible resources (time and talent)....why is it okay to waste the former and not the latter? Consider Packard's notion of a "philosophy of waste" (ch.1) in your response.

- Take a minute to notice your reaction to what you read in the intro and first three chapters of the Wastemakers. What's your position on his claims? Is our economy based on a seemingly insatiable need for more stuff? Does that make you uncomfortable or do you find yourself irritated with his claims (be honest!)?

- Describe at least one other consequence besides waste that comes from an economic system that's constantly encouraging material consumption (note: you won't find an answer to this in your readings, need to think about it on your own).

REQUIREMENTS:

- Respond fully to all three prompts (20 points).

- Respond thoughtfully to at least one of your classmate's posts (10 points)

Method 2: Use discussions as a means for students to work out ideas.

Example prompt:

This is a brainstorming discussion! You've had a bit of exposure to different types of things you might research for your paper this term. Given that it's week 4, I'd like you to use this discussion as an opportunity to narrow in on a possible topic.

This is how this discussion will work, and the earlier you post, the better this will go:

- In your initial post: list 5 different topics that you think you might be interested in investigating. You need to be somewhat specific: for example, rather than "recycling" (too broad) you might put "understanding clothing products (e.g. Rothy shoes) made from recycled goods." You just a need list, you don't need to expand on each of the five topics (10 points)

- In your follow up posts: choose ONE ITEM from a classmate's list and provide a suggestion related to that item. This could be an article link, a corporation or product to look into, a specific question you think might be interesting to explore related to the topic. In other words, you're helping them think about one of their possible topics.

- You must comment on two (DIFFERENT) classmates' posts on (and you can't use the same suggestion twice!)--5 points each.

Method 3: I use discussion as a means to check in on students

Example prompt:

Watch this week's announcement video to get background on the assignment!

You must do two things to get credit for this discussion:

- Post a picture of yourself with a sign of spring in the background (or foreground).

- Tell us how you're doing! Tell us where you are, how things are going, and share one thing you're doing to help survive quarantine.